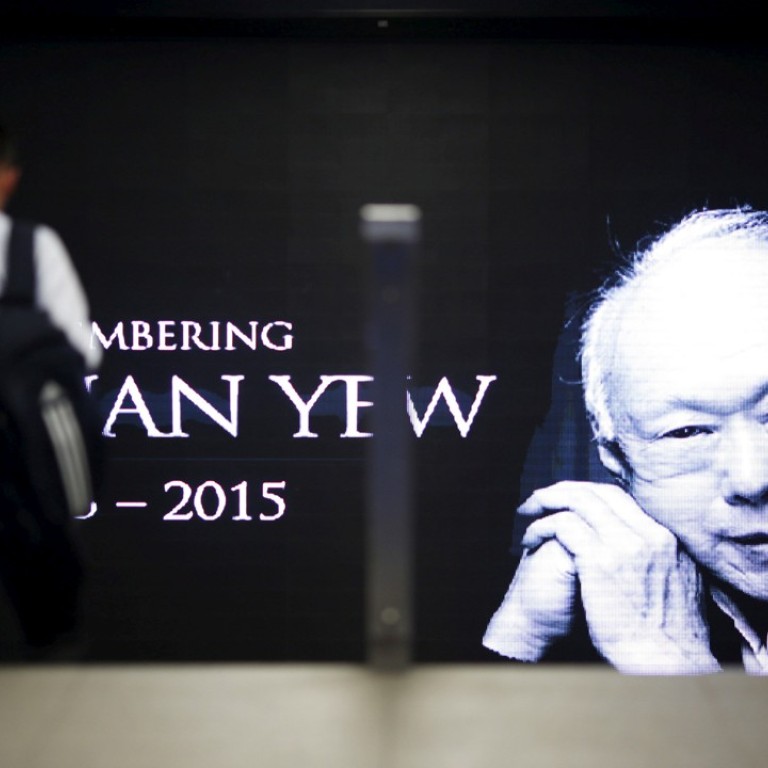

From Lenin and Mao to Lee Kuan Yew, legacies are determined by the living, not the dead

N. Balakrishnan says in almost every instance, the decision of how to treat the legacy of a founding father rests with their successors, regardless of what the one who died wanted

Why the Lee Kuan Yew family feud is a metaphor for Singapore

The most obvious transgression happened with Ho Chi Minh, who had written in his will that, after Vietnam was unified, his cremated ashes should be scattered across North and South Vietnam. Vietnam has been unified for decades, but it does not look like his body will be cremated any time soon.

Those of us who have read the great tomes of Russian literature such as The Brothers Karamazov will know that it is an old Russian tradition to believe that the bodies of holy men do not deteriorate after their death. The Russian Communist Party drew on this tradition to preserve Lenin’s body. It was his body, rather than his words, that provided the continuity in Russia, and perhaps still does.

The political lesson that the Chinese Communist Party learnt from the Soviet Union is that after Joseph Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev, publicly condemned his predecessor, the Soviet Union started going downhill. So, Mao is still venerated in China.

Can China ever move on from Mao Zedong?

What Mao would make of today’s China is anybody’s guess. But from Chinese taxi drivers who hang Mao talismans around steering wheels to avoid accidents, to millionaires who patronise restaurants themed after the Cultural Revolution, Mao is still present in China today, both in body and spirit.

Hindu India has a tradition of cremating bodies so, in some ways, the problem of what to do with the founder of modern India, Mohandas Gandhi, was an easy one. He was cremated and an eternal flame installed in the cremation spot. Most towns in India sport a statue of Gandhi and a big road named after him. Most Indians now shorten the name of the road to “M.G. Road” and many young people don’t even know what M.G. stands for.

As they say, we attend funerals not to please the dead but to please the living descendants. In Singapore, the fate of Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy will be determined by his successors who prevail, regardless of what Lee himself might have written in his will – as elsewhere. Legacies are just too important to leave to the will of the dead.

N. Balakrishnan is a former foreign correspondent and an entrepreneur in Southeast Asia and India